How to Be Human Read online

Page 2

From the earliest age, Ash remembers that all his parents talked about were their plans for death. They made him promise at the age of three never to put them into a nursing home and not to take ‘drastic measures’ to save their lives. Drastic measures seemed to include taking anything for illness other than turmeric and warm milk. They had seen too many people end their lives suffering in hospital, and thought it would be wrong if they lived too long and wasted the family money. Ash said the first words he learned were ‘Pull the plug.’

His father died suddenly of a heart attack, so the question of pulling the plug didn’t come up. He was cremated, and his mother, always frugal, declined an urn and put the ashes in a cardboard box. One random day, she decided to burn the box and the ashes in a fire pit at a park in Cleveland; she was going to roast some corn for dinner anyway. Because things were running late (her sisters were coming for dinner), she thought she’d get everything going at the same time. She said a quick prayer and roasted the corn on top of the burning ashes of the father. They went home and Ash’s sister made salsa out of the roasted corn and peppers. When his aunt found out about the barbecue/funeral, she left the house in a fury. But Ash’s mother, maybe because she’s a doctor, felt she was simply being practical.

She is eighty years old now, recently got a degree in psychiatry and still works at a hospital, sleeping there several nights a week.

Ash is married to Susan Elderkin, a successful novelist whom he met in London, and they have a son, Kirin, who is probably going to be a genius.

1

Evolution

What Exactly is This Thing Called Evolution?

Let me clear up something about evolution. I was taught in school that when we evolved as a species it meant we were improving the whole time; each generation developing more advanced features. I’ve found out this is a common misconception. Evolution doesn’t mean the species gets better, it just means we become better adapted to the environment, sometimes at great cost. What works for us as far as surviving is concerned also might work against us. One example is us getting up on all twos, great for hiking but the downside is we get backache. Had we remained in crawl position, we’d be fine and chiropractors would be out of business.

People today may be living longer than they did before, but it’s not clear that people are living better, or that in one hundred years from now they’ll be living more improved lives than they are today.

What Went Wrong?

Evolution did a fine job helping us adapt to changes in the weather and the dodging of dinosaurs. Full points for helping us out with survival, but not so many for helping us figure out what we’re supposed to be doing here on planet Earth. It’s this sense of unrest, this nagging feeling that we’re supposed to find some meaning, that makes us (especially existentialists) very, very unhappy. Baboons are still going around having the time of their lives while we’re tearing out what little hair we have (compared to baboons) trying to suss out why we don’t feel good enough. We’re at the top of the food chain, for God’s sake, what’s to feel not good enough about? Even grasshoppers don’t have low self-esteem (I’m guessing).

We can deal with danger but, in the face of envy or comparison, we’re helpless. You can’t club those emotions like you can a predator; they aren’t a physical entity and you’d just be clubbing yourself to death. When we get trapped by envy, it grows into rage, which can grow into illness, addiction and, eventually, mental disorders, especially for kids.

It’s a miracle evolution worked at all. What were the chances that, out of some stardust, we would make it through to now with our full set of teeth intact? As far as we know, no other planet managed to pull this off. They haven’t made a single cell of anything interesting, while we’ve already sold 12 trillion McDonald’s burgers.

Astronomer Fred Hoyle wrote, ‘To imagine that a human being could emerge by random chance in the universe is like trying to imagine a hurricane blowing through a junkyard and creating a 747.’

We give ourselves such a hard time for things that are out of our control. For me, this news was a revelation; the fact that I am not my fault but merely a player in the DNA legacy has done wonders in helping me stop being so self-critical. My addictive drive to achieve, whether it’s getting someone at a party to like me (who I’ll probably never see again and/or don’t even like) to saying, ‘Of course I can write a book in three months’ (and ending up institutionalized from the pressure). I now know that this drive isn’t something I’m doing on purpose to torture myself; it’s not just my condition, it’s the human condition. It’s something that’s been passed down by our Palaeolithic forebears for survival’s sake to keep us striving for rewards. Hurrah! I don’t need to be absolved by any shrinks, priests or rabbis; human history is the culprit.

Our Relations

Why are we so hard on ourselves when, in our evolutionary timescale, we’re still in our infancy? Here are a couple of facts to show that we as Homo sapiens are still a work in progress and not at all as cutting edge as we like to think. We share 98 per cent of our DNA with great apes, and about 90 per cent with mice. And it gets worse: we share 30 per cent of our DNA with yeast. I heard that there’s a T-shirt with the slogan, ‘You share 25 per cent of your DNA with bananas. Get over yourself.’

I read recently that researchers discovered a wrinkled sac-like body about one millimetre long that’s all mouth and no anus (I’m not making this up), so food goes in and comes out of the same orifice. It is called Saccorhytus coronarius. It turns out it’s related to us, even though it existed 540 million years ago and is now extinct. So there’s another reason for us not to get up on our high horse.

Darwin wrote, ‘Why is thought, being a secretion of the brain, more wonderful than gravity, a property of matter? It is only our arrogance and our admiration of ourselves.’

The History of Us in a Nutshell

We began as a single-celled piece of protoplasm sticking to a rock (it was a pathetic sight). We remained in that state for millions of years, then we advanced to algae (not an impressive leap). Later, we went through our fungal phase (yes, you are related to the mould on last week’s sandwich and old yogurt). Next, we became parasites, and moved on to being jellyfish, to worms, to jawless fish, to sharks (Wall Street stage). Our ‘fish out of water’ amphibian period ended when we replaced our fins with feet and crawled out of the water. After that, there was no stopping us. At this point in our early mammal days, we looked a little like hamsters and spent our time dodging dinosaur feet. Then, accidentally, a meteorite fell down. Those of us who survived continued to develop. The rest were squished.

Somewhere between 40 to 25 million years ago we went from being apes to being orang-utans to being chimps. About 6 million years ago we went bipedal and homo. (Not that kind of homo – stay focused.)

Only for the last 200,000 years have we been modern humans: Homo sapiens. ‘Sapiens’ translates roughly into ‘thinking about thinking’. We were, and are still, the newest kids on the block. This doesn’t mean we’re now flawless. We didn’t dump all our old primitive equipment; those reptilian parts are still alive and well within our brain. So that’s where we are today: part savage, part genius. That ancient region left over from about 300 million years ago had its uses, endowing us with the ability to breathe, swallow, hump, sneeze (the basics). Eat, Pray, Love would never have made it as a bestseller back then. Eat, Fuck, Kill might have been the bigger hit.

Our mammalian brain is about 100 million years old (giving us some emotional range and the ability to bond). About 200,000 to 500,000 years ago, an area of our brain known as the neocortex had a growth spurt, giving us the ability to plan, to self-regulate, to control our impulses and become aware of ourselves. With this more advanced part of our brain, we learned to speak, to use symbols, solve problems and imagine the future. The downside was we started to worry and ruminate about ‘what if?’ scenarios, not to mention the mother of all worries – knowing that we’re all going to die – whic

h all adds up to make us a very jittery race.

Trade-offs

It seems that, in evolutionary terms, every time we take one step forward, we take a multitude back. These evolutionary trade-offs don’t just happen to humans but to all living things. An animal which I think got one of the worst deals is the giraffe. It never evolved claws, sharp teeth or a hard shell and needed some feature to avoid getting extinct-ed (I know it’s not a word, but I’m using it anyway) and so came the long neck. Now, the giraffe could eat the leaves on top of the trees and no other animal could. The trade-off was that, if it ever tipped over, it would never get up again. Or be able to hold a glass of Chardonnay.

There have been countless trade-offs. For example, millions of years ago, when the tropical forests disappeared because of shifts in the Earth’s crust, the Great Rift Valley in Eastern Africa was created and apes found themselves treeless. Without a jungle, there was no need to swing from branch to branch so boom!, the bipedal creature was born. I guess someone thought two legs were better than four. Now that we were hands free, we could make tools and (more importantly) jewellery while being able to stride long distances. We needed to walk, and walk fast, because the violent temperatures on earth forced us to move across the planet without burning our feet.

Another bitch about standing up is that women now have difficulty in giving birth. (Oh, really? I hadn’t noticed …) On all fours, it was easier to deliver but, standing up, the pelvis is too narrow, so pushing out the baby is more painful than passing a beach ball.

Again, I’m absolving myself from bad personal choices now that I know my brain is making decisions I’m unaware of, some of which are far from beneficial. Part of the problem is that the different regions in the brain aren’t all on the same page.

The Good Times: When We Were All in the Same Boat

When we as a human race were young, life was dandy – apart from the threat of being devoured, or frozen by an Ice Age. During our ape epoch, we lived in tribes of about thirty to fifty, most of them family members or, at least, very close acquaintances. Everyone was on a friendly ‘Hi’ basis. In this environment, we could trust each other because nearly everyone shared the same genes. Of course, the bad news with all this in-breeding was the kids often had webbed feet or only half a head.

These were the good times of the hunter-gatherers, and they lasted many thousands of years. The men did the dirty work, spearing dinner; the women peeled roots and bulbs (this was before Women’s Lib). No one complained, mainly because they couldn’t speak back then; language hadn’t been invented yet. If a man wanted to date a woman, he would raid the next tribe, drag the woman back to the camp by her hair, have sex with her and probably never call her again. These were not particularly romantic times (pre-Valentine’s Day).

For you animal fans, thirty to fifty was also the ideal number for a group of chimpanzees. At that number, it was possible for everyone to groom each other for bonding purposes. Everyone had a chance to pick bugs off everyone and no one felt left out. When a chimp population went up to a hundred or more, the social order was ruptured and there was internal squabbling.

We humans, in the meantime, could expand our tribes to up to 150 members and still maintain equilibrium and trust. If someone was in distress, the rest of the tribe would come to their aid with flowers and chiselled-in-stone get-well cards. They could groom by proxy.

A hundred and fifty was ideal then, and still is today for successful family businesses, social networks, town-hall meetings, military troops and harems. Everyone, if not close, was on nodding terms; no one was a stranger, so there was no need for ranks or laws.

We all had a job to do: picking, skinning, hacking (obviously, not the way we hack computers now, but to clear the bush). No one was dissatisfied with their role in life and, if you weren’t svelte, rich, savvy or Jennifer Lawrence, you didn’t feel like a toad.

No one laughed at you because your teeth jutted straight out of your mouth, because everyone’s did. No one suffered from low self-esteem. It hadn’t been invented yet.

Ranking and Status: The Birth of Envy

One day, for the sake of competition for food, territory and sexual partners, we started to rate ourselves against the next guy. We suddenly became conscious of who was weakest and who was the most popular. This developed into feelings of shame, low self-worth and self-criticism for those who felt low down on the totem pole of status.

From this point onwards, the idea that we were all equal was axed. Now, to ‘make it’ in the community, people felt under pressure to bring something special to the tribe that would make them stand out. Anthropologists found physical evidence of this when they dug up the bones of women who lived thousands of years ago. They found private burial sites where women were bedecked in jewellery. The unjewelled were all flung together in a communal grave. Other evidence shows that the stronger and more savvy a man was, the more likely it would be him that was first in the food queue and fed the most. This also went for the women with the widest, child-bearing hips. (Unlike today, where you have to look like a stick with one eyebrow.) So, ranking began because of the need to stand out in a crowd. I’m almost certain that’s why comedians evolved and still exist today. If you didn’t have bulk or child-bearing hips, you might have been flung to the predators as an appetizer, so certain neurotic people in the tribe started to make funny faces or pretended to slip on banana skins, and everyone laughed. It must have worked because, from then on, the face-pullers and slippers got a piece of the buffalo pie. If you didn’t have anything special to bring to the social table, you are probably not alive today. Then as now, social status meant survival. Alpha men, ripe young women, those with high IQs and a few comedians are still on the survival A-list.

Another reason why comedians were suddenly ‘in’ was because, when the tribes became larger, they used rituals, music and comedy to bond the community. It turns out that music and laughter activate the same endorphins as grooming does. Even among great apes, the replacement for mutual grooming was shared laughter, and they had banana skins by the boatload to use for their shtick. The rapid exhalations you make when something amuses you empties the lungs, leaving you exhausted and gasping for breath. This stress on the chest muscles triggers endorphins, which are contagious. If an ape walked into a tree and fell over, everyone found it hilarious and it made them feel great.

Agriculture

(I know it’s not the most alluring of topics.) This marked the end of the good times but the beginning of civilization, and there was another big trade-off.

Towards the end of the last Ice Age, about twelve thousand years ago, populations started to increase and settle into villages. Hunting and gathering were out, and farming was in, meaning people remained stationary to grow their own food, which they could replenish each year. People fenced off their plots of mud to keep invaders out and claimed it as their property (birth of the ‘me’ and ‘mine’ concepts). They built houses for safety, to separate themselves from scavengers, and from then on, they became more self-centred creatures. They began to accumulate ‘stuff’ (furniture, animals, probably jewellery), to which they gave enormous value and defended to the death. Raiding was a problem, and lasted for the next five thousand years. Eventually, an elite group appeared who accumulated more than everyone else because they were the bigger bully, taking the peasants’ surplus food and, worse, taxing them on it. At this point, 90 per cent of the population were peasants who worked the land and the remaining 10 per cent lived off them. The ‘them’ and ‘us’ society began for real.

Afterwards came improved transportation, enabling more people to form villages, which turned into towns, then cities, then kingdoms. The problem was that humans had evolved for millions of years in small tribes, and the sudden increase in the speed of the growth of these empires during the Agricultural Revolution didn’t leave enough time for mass cooperation to evolve alongside. This could be why we’re mentally skewed today; we didn’t have enough time to adjust to our

speed-of-light advancements. Some people think that the Agricultural Revolution put mankind on the road to progress, while others argue it was the road to perdition. If we had carried on cooperating with each other, we’d be much happier and better adjusted today.

History Continues …

After this, each epoch in history had to deal with population explosion and the raping and pillaging that went with it. During the Greco–Roman period, people blamed their misfortunes on the gods, from thunderstorms to boiling to death in their Roman baths. If we drank too much, it was because Bacchus, the God of Grapes, made us do it. If you suddenly fell in love with Mr Wrong, it was because Venus had sent one of her naked Cupid boys to zing you with an arrow, so it wasn’t your fault.

My husband, Ed, never thinks his actions are his fault either. He endlessly walks into low ceilings and complains that cars drive into him, then blames it on the ceilings and other drivers who can’t drive. He won’t believe that these are his fault for forgetting to bend down and refusing to believe he can’t drive.

Jesus

On the cusp of BC and AD, Christ took over and told us He knew what He was doing and we didn’t. We were all scum of the earth and natural-born sinners but, if we admitted our scumminess, we could get into Heaven and He’d forgive us.

Jewish people also feel they’ve done something wrong but usually believe it is someone else’s fault. They have holidays where they celebrate how badly they’ve been treated. They have Passover because they had to leave Egypt with no warning. They were exiled so quickly their bread didn’t have time to rise (but matzo, to my mind, is more delicious than bread, so what’s the problem?). At Passover, they believe someone else ripped them off so they eat horseradish to remind them of their bitterness (like they need reminding?).

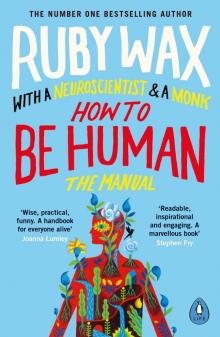

How to Be Human

How to Be Human